“The practice of honoring our war dead in the U.S. goes back at least as far as 1877 when a ceremony was organized to honor the dead of the Confederate Army at Memphis, Tennessee. What was called “Decoration Day” in my youth is now called Memorial Day and is meant to commemorate the sacrifices of the dead of all our wars.In our cemetery here lie veterans of the Civil War, World War I, World War II and the Vietnam War. Thankfully all of us Korean veterans are still alive. Many of you have relatives lying here. No town that I know of has done such an outstanding job of honoring the veterans since the end of the first World War as has Long Lake. This was largely due to Daniel J. Hughes who came here before World War I as school principal, served in the war, and after the war began the continuing practice of the school children marching to the cemetery as an integral part of the American Legion Parade. Many of you will attest that he was a fine man. I well remember marching up here when I was in the second grade with the Long Lake World War I vets. Try to find any city parade which has so much feeling.

“The person who should be speaking here today is some World War II veteran since everyone knows that this year marks the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II. It is hard to realize this fact because for some people in my general age group it seems almost like yesterday. I know that for you younger people this is difficult to understand. We older folk still tend to date things as being “before the war” or “after the war.” For us it was the greatest event of the 20th century.

“This past winter I read a fascinating book on President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the grueling 4 years of war during which he led the U.S. to eventual vistory. It brought back to memory the staggering breadth of the was effort—in plane production alone we went from a few thousand in 1941 to over 350,000 in 1943. By 1944 American war production was greater than that of Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia and England put together. We were blessed in those days with a superb group of production people who knew how to knock heads together and turn out products at a rate undreamed of.

“As for the armed forces, when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in 1941, which brought us into the war, we had a pint sized army of 160,000 men which ranked somewhere around 20th in comparison with the armies of foreign nations The Navy and Marines were similarly small in numbers and equipment. By the end of the war in 1945 through patriotic fervor and the draft, 17,000,000 men and women had gone into the armed forces. Little Long Lake alone contributed 121 men and women of whom six were killed. I will name these men and give them the honor they deserve. It makes me feel old and sad for I knew them all.

- “Alfred Cole, a brother to Margie Wilson, Florence Cole and Jake Cole

- “Robert Duane, a brother to the late Evelyn Mazik and Dolly Grenier

- “Ed and Tim Hamner, only sons of old Ed Hamner

- “Ed McGinn, only son of Allie McGinn

- “Phil LaPelle, Brother of George LaPelle, the late Dale LaPelle, Richard LaPelle, Johnathan LaPelle, Lenora Seaman, Ann Sabattis, Barbara Hebert, Ruth LaPelle, and Darlene LaPelle.

“In the words of the Irish Poet Padraic Colum, ‘May the wild earth that covers their bodies lie lightly over them.’

“You should at your leisure look over the plaques of men and women who served from Long Lake in World War II on the monument which stands in front of the Town Hall. I remember, as do some of you, the plywood temporary plaque that stood in front of the Post Office during the Second World War, and every time someone joined the services Fred Burns would paint his or her name on the plaque. After the war the plaque became disreputable from the weather. In 1961 the present war memorial was built after the World War I monument was torn down with the agreement of the World War I vets. The plaque from the World War I monument was afixed to the present memorial.

“As for the monument itself, I believe it to be the finest in the Adirondacks and I should tell you in the interest of history how we acquired the statue which depicts World War I soldiers. In 1960 Mr. C.V. Whitney of Whitney Park agreed to donate one statue of 4 which were located on his Old Westbury, Long Island estate. These statues had been done by his mother, Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, a noted sculptress.

“A few of us, including Daniel Hughes, of whom I have spoken, Howard Seaman and Denny Lamos subsequently drove to Long Island to choose one of the statues. We actually left the choice to Mr. Hughes who chose our statue because he felt that it best showed the agony and horrors of any war. It was a good choice and we are lucky to have it.

“We are a proud town with a beautiful cemetery and a proud heritage of honoring all of our war dead. As for the future, like everyone else, I hope we will not have to fight again, but history is against us. I have no doubt that Long Lakers would again spring to the colors if war came. Parenthetically, we should give a round of applause to Denny Lamos, a genuine World War II soldier. (Denny appeared at the cemetery dressed in full World War II uniform and helmet.) In closing I say, ‘Hail to our World War II vets.’”

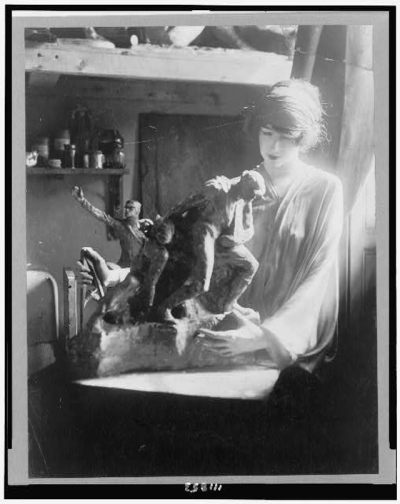

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875-1942), member of two of the wealthiest families of the early twentieth century and mother of our late neighbor Cornelius Vanderbilt “Sonny” Whitney, wanted to be known as an artist, not just a rich lady. She combined her wealth and her passion in founding the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City in 1931, and throughout her life she worked on her own sculpture. Whitney’s best known piece is The Scout, mounted at the entrance to the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming. But Long Lakers don’t have to travel to Cody to see Whitney’s work. A rendering in stone of one of her sculptures stands right in front of the school.

The sculpture on top of our war memorial was titled by the artist Over the Top, and it depicts a soldier hauling his comrade over the earthwork of their trench for a charge against the enemy. Not for her the victorious leap forward; Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney was one of the few artists of the time who depicted the true horrors of World War I. Initially just to work through her own feelings about the war, she made a number of small sculptures, like the one above, that showed the agony and despair of the soldiers. She knew that side of the war through her work establishing and supporting a hospital in France. She visited the institution several times in 1914, volunteering in the wards. Whitney exhibited these works in a gallery attached to her Manhattan studio in 1919 entitled Impressions of the War. She felt that her war sculptures were her first in which she truly expressed herself in her art.

Long Lake’s Over the Top may be the only copy of that piece. Whitney worked in clay and then turned over the small original sculptures to be cast in bronze or cut in stone. In this case she had it produced in limestone and placed on her estate in Old Westbury on Long Island. The name of the stonecutter of this one doesn’t survive.

In 1977, Barbara Jennings wrote about the sculpture’s trip to its permanent home in Long Lake. She remembered that Howard Seaman, a veteran of the Second World War and commander of American Legion Post #650, made the initial ask in 1959 through the caretaker of the Long Island estate. Sonny and his sister Barbara Whitney Headley agreed that one of the statues on the grounds could be given to the town. (The plaque on the monument mentions only Barbara.) Howard and his companions drove to Long Island in the fall of 1959 and back in the same day, bringing Over the Top with them. They stored it in Walter Macaulay’s garage over the winter. He was in Florida at the time and nobody mentioned the new tenants to him, affording him quite a surprise when he returned in the spring.

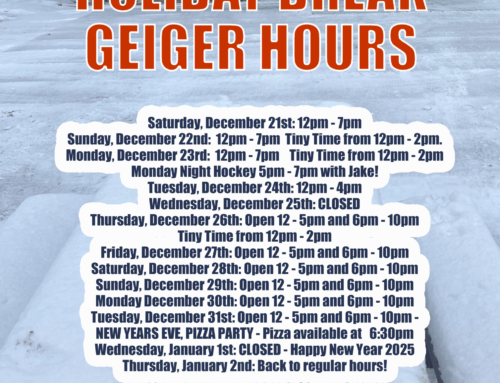

Fig. 4 Sketch by Frances Boone Seaman (1918-2005) for the base of the new war memorial, April,1960.

The base for the sculpture was designed by Frances Boone Seaman (former Town Historian) and built by McKinley Hanmer and Joe Burnett from stone reclaimed from the old bridge abutment. It was installed in a downpour. The name of the sculpture isn’t on it, and its original name was soon forgotten. The schoolchildren of 1960 nicknamed the two soldiers Curley and Mo, but around town they’ve become known simply as The Doughboys. From their perch atop Long Lake stone, they have overseen Memorial Day Parades and all the other traffic through the central Adirondacks for the past 63 years.