We all assume these days that we can talk with someone miles away from anywhere with a few taps on a little machine we hold in our hands. While that’s not literally possible everywhere in the Town of Long Lake, your child can call from the ballfield to tell you practice is running late, and a clueless visitor can call from the top of Owl’s Head for an Uber. Or try to. It’s all rather like magic—a service that happens without any apparent input by people. Not long ago, telephones not only connected Long Lakers with those they were calling, but involved connections with others along the way.

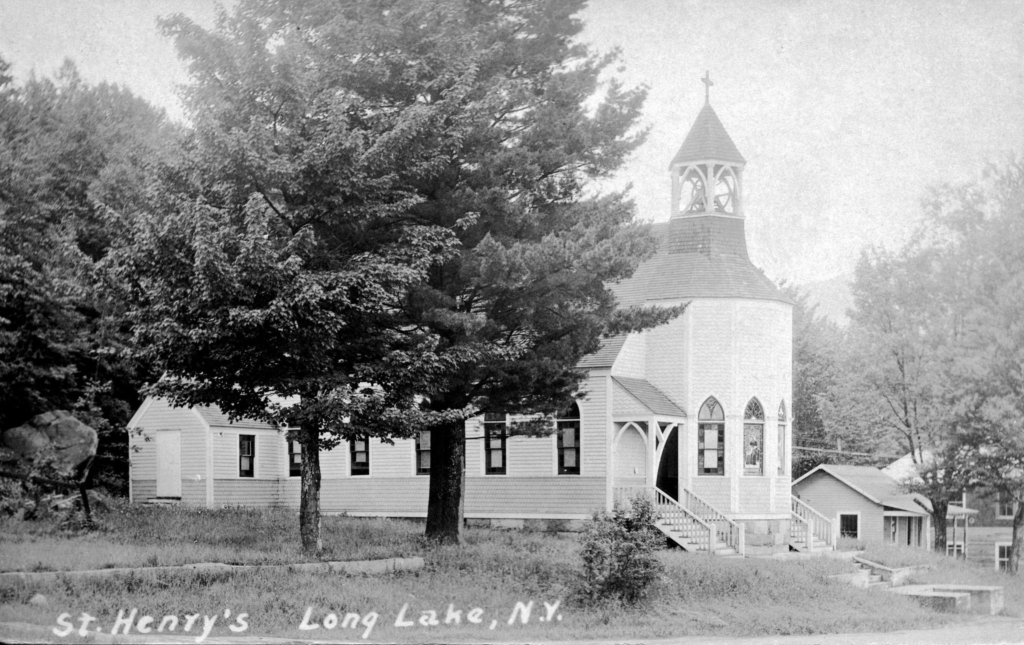

St. Henry’s church in its original location (across the street from presently) with the small telephone building to the right, originally the Western Union telegraph office, ca 1915.

It was 1876 when Alexander Graham Bell patented his telephone. It was such a revolutionary device that people everywhere wanted one. Cities built networks to connect their residents and gradually small communities like Long Lake organized themselves to be connected to the outside world, too. By the time of the First World War, the country was peppered with small, independent telephone companies. In 1913, here in Long Lake, Timothy Sullivan and his wife Bridget, their son and his wife, and several other townspeople incorporated the Long Lake Telephone Company. Initially, it connected subscribers along four miles in town, but gradually it extended lines to Blue Mountain Lake, Raquette Lake, and Newcomb, as well as down to the foot of the lake, Shattuck Clearing, and Forked Lake.

In 1913, the earliest and biggest national company, Bell Telephone, agreed to start connecting the lines of small companies like ours to their more extensive network. After World War II began a period of consolidation in which the small companies were bought out by bigger and bigger networks. The Black River Telephone Company bought out Long Lake in 1920, and itself became part of General Telephone Utilities and then Continental Telephone of Upstate New York.

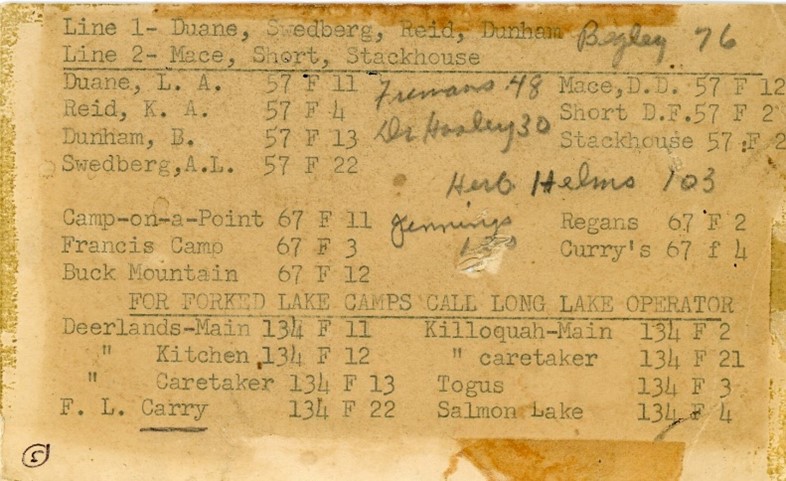

Index card with Long Lake area phone numbers and party lines from the operator-assisted days. Courtesy Joyce Rayome

Even though our local telephone system was owned by a big corporation out of the area, the telephone service remained personal. Until 1956, Long Lake telephone calls were placed through a central switchboard housed in a small building next to St. Henry’s Catholic Church when it was on the other side of the road. The switchboard operator was well informed about the doings of the townspeople; it is said that she (and it was usually a woman) kept track of the town doctor and could find him if he was needed in an emergency.

The system was converted to dial phones in 1956, and served about 250 customers who no longer had to pay toll charges to call Blue Mountain Lake or Newcomb. A great innovation was a “tape-recorded message to alert customer of a misdialed or disconnected number.” A local operator was still necessary to deal with the party lines.

Although the system owners were out of the area, the telephones themselves were owned by the customers and installed and repaired by a local person. The last of these installer-repairmen in Long Lake was John Rayome, who came to work in town in 1965 and served the community for 27 years.

Rayome was responsible for a territory covering 3200 square miles. It included the Long Lake, Blue Mountain Lake, and Newcomb exchanges. It also included some separate systems such as that at Whitney Park and the Tahawus titanium mine, where National Lead installed a new internal system in 1975 with 50 stations connecting its departments.

As today, trees frequently brought down the lines. A large part of Rayome’s routine was cruising the lines and trimming menacing branches. He also dealt with problems not encountered by his colleagues in more settled areas. He frequently found that bears had torn protectors from utility poles and assumed that the animals mistook the humming sound for bees.

John Rayome and Herb Helms preparing to take off for a service call about 1968. Photo courtesy Joyce Rayome

The lines in Rayome’s district ran over land, under lakes, and underground and Rayome became famous in telephone circles not only for the distance he travelled but how he travelled. A supervisor once commented on the “mess” in his truck: extra sets of clothing, peanuts for emergency food, a transistor radio, extra flashlights, snowshoes. Rayome never knew what conditions he might encounter out in the woods. In 1968, General Telephone of New York publicized him as its only “flying repairman.” “Some subscribers are 23 miles away over 15 miles of secondary roads and eight miles of logging roads,” read a press release that was widely picked up. “Under good weather and road conditions it’s an hour and 15 minute trip by van truck, but only minutes by seaplane at 130 m.p.h. cruising speed.” The seaplane, of course, was piloted by Long Lake’s Herb Helms. Spring and fall Rayome connected and disconnected the phones of seasonal camps down the lake, and occasionally he had to find a break in the submarine cable that ran all the way down the lake. That involved taking “soundings” along the way until he found the break and then hauling up the cable to repair it. For these jobs, Rayome rented an outboard boat from Emerson’s boat livery next to the Long View Lodge.

John Rayome (driving) and cable-laying crew on Long Lake, 1972. Photo courtesy Joyce Rayome

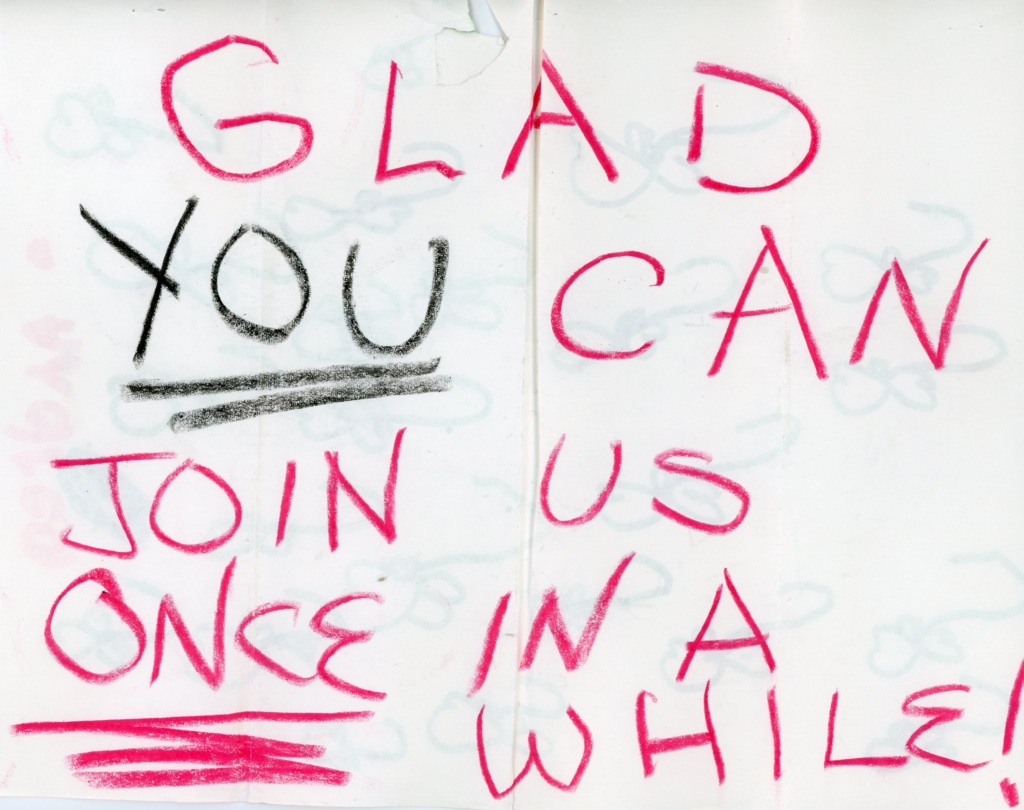

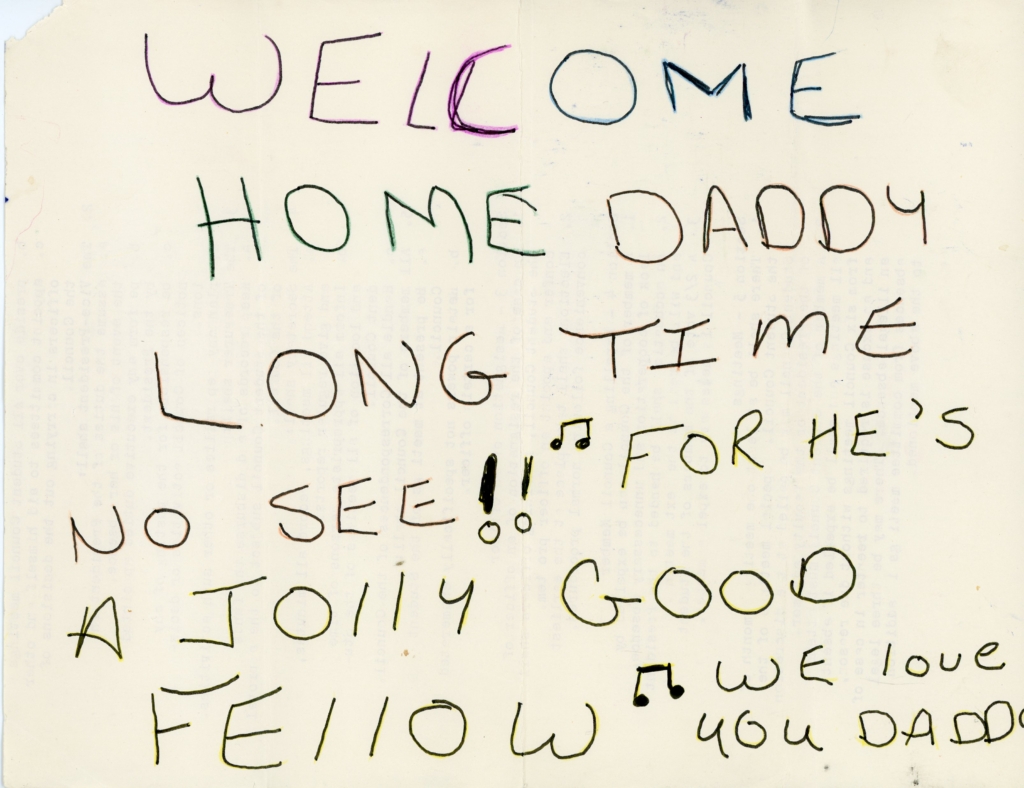

In a sense, the whole Rayome family (John’s wife, Joyce, and nine children) worked the telephone job, too. The long and unpredictable hours kept him away from home until late at night many days. When he missed dinner with the family he often ate at a restaurant in town before going home. In August of 1975, a series of storms kept Rayome on the job for 60 ½ hours one week, 69 the next, and 47 ¼ hours in the first four days of a third. When he finally made it home for supper he was met by handmade signs stuck on the window, the door, and under his dinner plate expressing the feelings of his 3-, 6- and 10-year-olds.

These two notes from Rayome’s children published here were part of an article Contel printed in its house organ in after that marathon session of telephone repair. Rayome’s comment was that he always treated his customers like neighbors because they were neighbors in this small mountain community. “You might see them at church the next Sunday,” he said.

John Rayome retired from Contel in 1992. He was not replaced. While some of us still have landlines, most also have mobile phones. More and more, people rely exclusively on their handheld devices to connect them with people who can’t hear them shout; and without visible assistance. Almost like magic.