Written by: Hallie Bond, Town of Long Lake Historian

Fig 1 Walker gatehouse ca. 1920. Photo courtesy Long Lake Archives

If you drive far enough on Kickerville Road, you will notice a charming little stone house. From the stone archway attached to it, you will guess that it was once a gatehouse, although the road now goes around it. Gate to what? Not so long ago, Kickerville Road was named “Walker Road” because through this gate you could drive to the estate of Thomas Walker on Rock Pond.

For over a century, Rock Pond (known to old Boy Scouts as Lake McRorie) and the woods and hills around it have been officially off-limits to the general public. Now, thanks to a conservation easement, we all can paddle and hike this beautiful area at the end of Kickerville Road. Except for this gatehouse and a stone chimney on the shore at the south end of the lake, most of what Thomas Walker built on the pond is now gone. From the memories of people in town, photos, and other tools of the historian’s trade, however, we can get a picture of what life was like there for the Walkers and the community that grew up around them.

Like so many wealthy New York city folks in the late nineteenth century, real estate broker Thomas Walker wanted to get out of the city to the Adirondacks and so he purchased a large tract of land and built up an estate. Like his neighbors R.C. Pruyn (Santanoni), and William Seward Webb (Nehasane), he logged the land to create some income. He eventually acquired almost 35,000 acres which he began to log in the late 1880s. He also purchased Round Island and Little Round Island in Long Lake. By 1892 he was building his camp on Rock Pond.

Fig.2 The Cole Farm with Long Lake at the top of the picture and Big Brook top right. Courtesy B.J. Rehm

People were already living in the neighborhood when Walker began buying; the relatively flat land was good for farming and had been settled in the 1840s. Walker bought out landowners like Lyman Russell, Fred Gokey, Elliot Henderson, Simeon and Almina Keller Cole, Ike Sabattis, Elmer Plumley, Walter Hamner, and Alba Cole. Most of these farmers seem to have continued to live and work there. Were they tenants or wage earners?

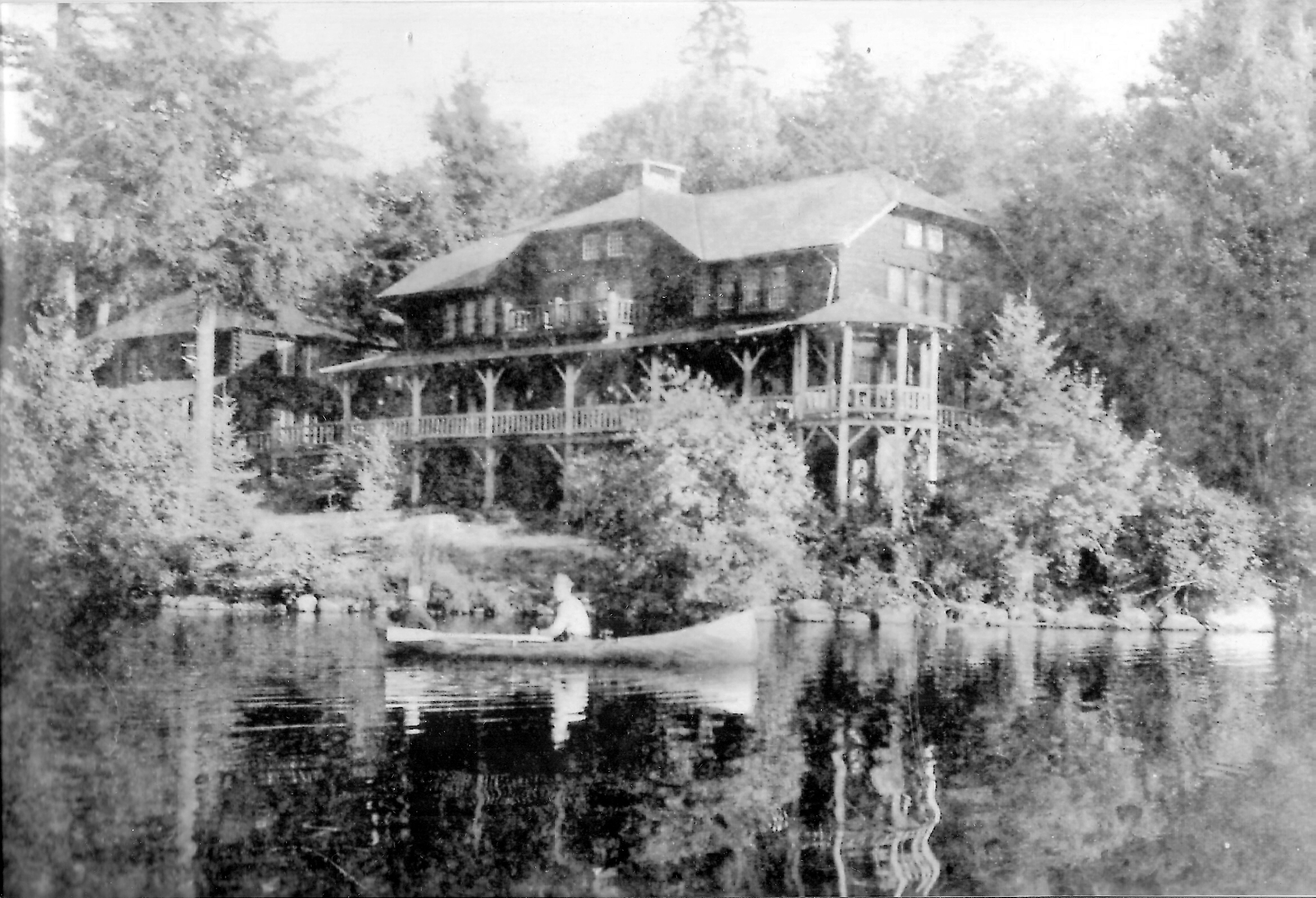

Fig. 3 Thomas Walker’s camp from the water. The chimney is all that remains today. Courtesy Long Lake Archives.

For a home on the lake, Walker hired architect G.H. Rogers of North Creek. Merlin Austin, who lived on a farm near the present gatehouse, built the camp with his son Harold, Senior, father of Long Laker “Bunny” Austin. (Merlin also built guideboats, and one wonders if the guideboat in the picture above is his.) No doubt other local men worked on the building, as well. Rogers conceived of the building as “Swiss in character.” It was a three story, T-shaped structure built to look like a log building but in fact of ordinary plank walls covered with half-round polished logs inside, and half-rounds with the bark left on outside. A screened-in octagonal porch sat on the corner overlooking the lake. It contained sleeping quarters, a kitchen, and a dining room. Austin and his crew built other structures in the main camp complex, including a rustic gazebo, a stone-faced root cellar, a boathouse for small craft, and servant’s quarters.

Fig. 4 Summer visitors on the Cedarlands porch were relaxed but formally dressed. Courtesy B.J. Rehm

Walker’s woodland estate depended on Adirondackers. In the early decades of the twentieth century, sixty people worked at Camp Cedarland. A number of families lived there in houses Walker provided (complete with wood for heating). They also had use of a horse and wagon, a cow, and the ice house. They were teamsters working in the lumber woods; farmers growing food and looking after the horses, sheep, and cattle; maintenance men and servants in the house. After the gatehouse was built in 1905, the gatekeeper who lived there was not only responsible for letting people in and out, but for raking smooth the gravel of the drive after every passage. Walker had a coachman until he got his first cars in 1923 (a 1918 Pierce Arrow and a 1922 Locomobile after which he employed Bob Allen as chauffeur. The children of the estate attended a school on the property.

Fig. 5 Staff in what looks like a flower garden at Cedarlands. Judging from their clothing, the man on the right may be the Swedish butler, and the woman on the left one of the waitresses. Courtesy B.J. Rehm

An ethnically diverse group of people, most of whom probably moved between New York City and the Adirondacks with the Walkers, lived at Rock Pond. When the Walkers first moved to Long Lake, they brought with them a Black coachman named Colthrop S. Slow and his wife Frances, Irish women Nora Charles (cook) and Beatrice Paliam (waitress). A Swedish family, John Danielson, his wife Huldah, and children Reginald and Marion, lived in the service complex at Rock Pond; he was the superintendent. Danielson was succeeded by another Swede, Albert Magnusson. The Walkers must have like Swedish help, for after Thomas died in 1929, Amandus Napoleon Engelbert Watz and his wife Selma Kristina joined the household, he as butler, she as maid. They had immigrated in 1927, and were to play a large part in Cedarlands history under the Americanized name of Watts.

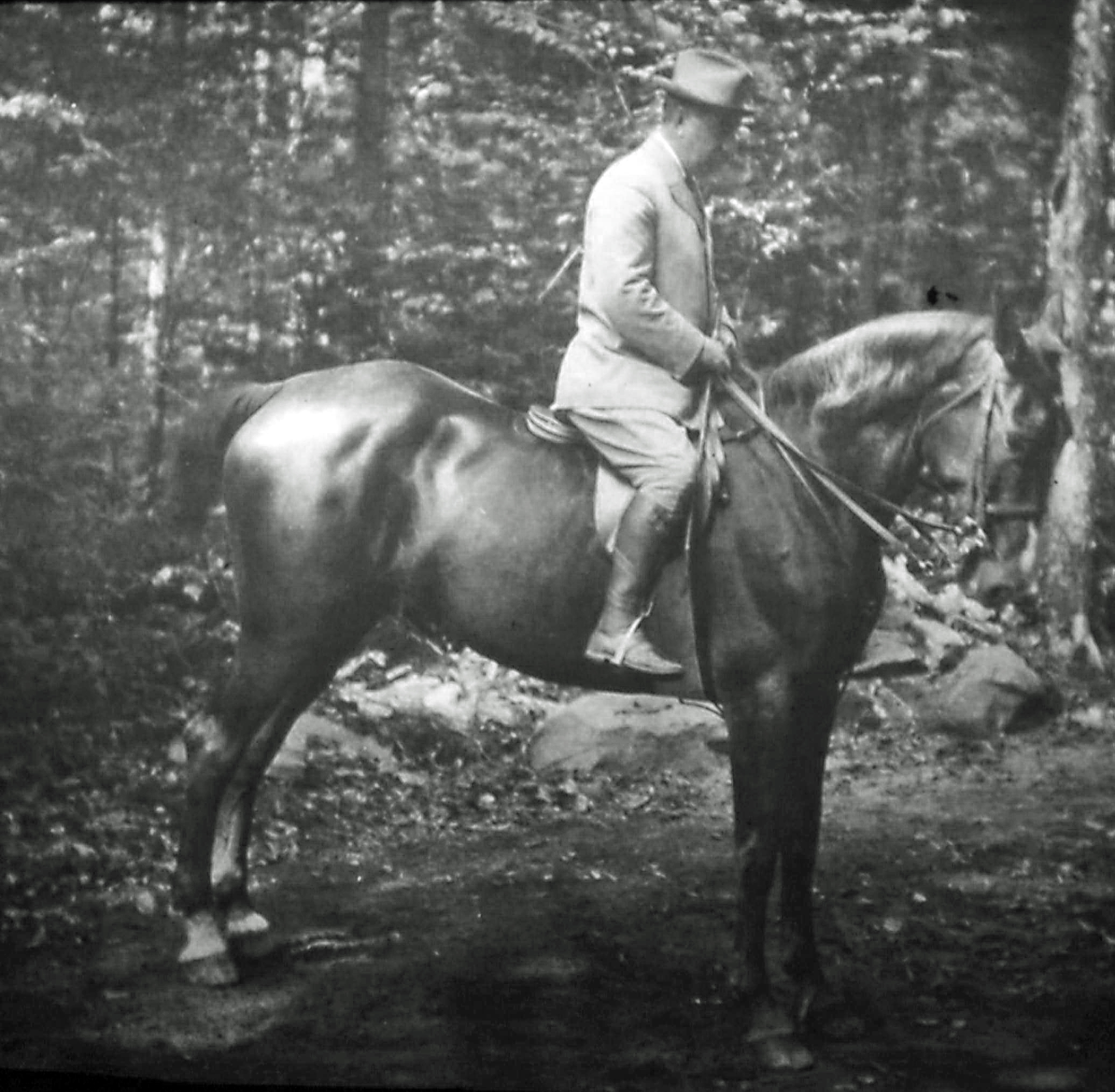

Fig 6 Thomas Walker on one of his riding horses. He once rode all the way from New York City to camp. Courtesy Town Archives

Thomas Walker never married. He lived with his parents, Stewart and Eliza, and his sister, Mary Louise, in New York, where he was a real estate broker, as was his father. His parents had immigrated from Ireland in the 1850s. It was after his father’s death in 1892 that Thomas began spending more and more time in the Adirondacks, where he, Mary Louise, and Eliza lived for much of the rest of their lives. The women slept in the big camp, and Thomas had his own, smaller camp nearby. Mary Louise remained single all her life, like her brother. She was an educated philantropist, channelling her energies primarily through the Methodist Church. She had graduated from Rutgers Female College in New York City, and was involved in the real estate business herself. At her death, she was vice-president of the Harlem Philharmonic Society, a member of Sorosis, the city’s oldest women’s club, a trustee of the Calvary Methodist Church in the Bronx, and vice president of the Methodist Church Home for the aged in NYC. She and her brother were active in, and generous to, the Long Lake Methodist Church, where Thomas Walker’s funeral was held after he died at Cedarlands in 1929.

Fig 7 Mary Louise Walker at Cedarlands. Courtesy Town Archives

A bit removed from the camp and the lake was a service complex with a large barn for Walker’s horses. He was a fancier of fine horseflesh, and would send his favorite driving team ahead of him on the night boat to Albany when he came from town. Presumably, the team was then loaded onto the railroad to North Creek, where it was driven through Blue Mountain Lake to Long Lake. Long Laker and bachelor Bill Cole was Walker’s teamster, and he apparently loved horses, as well. The working team, Charley and Molly, sported braided tails and fancy harness, as they filled the icehouse, drew wood, and plowed the road to the gatehouse. Walker didn’t acquire an automobile until 1923, preferring to ride in his surrey on his weekly trips into town.

Fig. 8 Thomas Walker is in the boater on the right. Is he supervising the men with the scythes, or just watching? Courtesy of B.J. Rehm

These trips were social, to attend services at the Methodist Church or meetings at the Masonic Lodge. The Walkers didn’t have to shop; Lahey’s and Freeman’s stores in town, and sometimes Baroudi’s in North Creek, delivered groceries and other necessaries. But like other great camps, Cedarlands produced much of its own food. There were at least two farms on the property, as well as herds of purebred dairy cattle and sheep. Walker was one of the few sheepmen in town in the early twentieth century. Workers processed and stored the farm products in a smokehouse, an icehouse, and a root cellar.

Fig. 9 Amandus Watts at the grill on the sundeck at Cedarlands, Main Camp in the background, ca. 1960. Courtesy B.J. Rehm

Thomas Walker left the estate to his sister Mary Louise when he died, and she spent her summers here until she passed away in 1946. “Because of his kind and faithful services to me,” she gave Amandus Watts the Cedarlands estate, the townhouse on W. 105th in New York City, the Packard, and “a gold snake bracelet.” He was directed to log the property and give the proceeds to the Methodist Church Home for the Aged in New York City with the stipulation that they purchase a car to take the inmates on outings. It was at this time that he re-routed the road to its present position around the gatehouse so that logging trucks could pass. Selma died in 1954. In the 1960s, Amandus began selling off parcels and renting hunting and fishing cabins on the property. He sold most of the estate to the Oneida Council of the Boy Scouts of America for $10 in 1962, and later gave the main house to the Scouts with the stipulation that it be known as Watts Loj. He died in 1966.

Fig 10. The cedar man on the hearth in the Main Lodge, Cedarlands before 1954. Courtesy B.J. Rehm

The big camp burned in 1980. Remains of the Walker era are difficult to find today. A few artifacts were rescued from the fire. The Adirondack Experience (aka The Adirondack Museum) owns a root-base rustic table and a rustic figure of a woodsman that came from the camp. The figure has natural crook elbows and is covered in cedar and may have been made by Watts. Amandus and Selma Watts are buried in the town cemetery. You can admire the gatehouse as you drive by (be respectful; it is now a private residence) and, of course, you can enjoy the beautiful woods and waters around Rock Pond that have been inaccessible for more than a century.

If you would like to enjoy Cedarlands: note that much of the property is closed to the public from June 24-August 22. Please see LINK https://www.dec.ny.gov/lands/108144.html for complete information and directions.